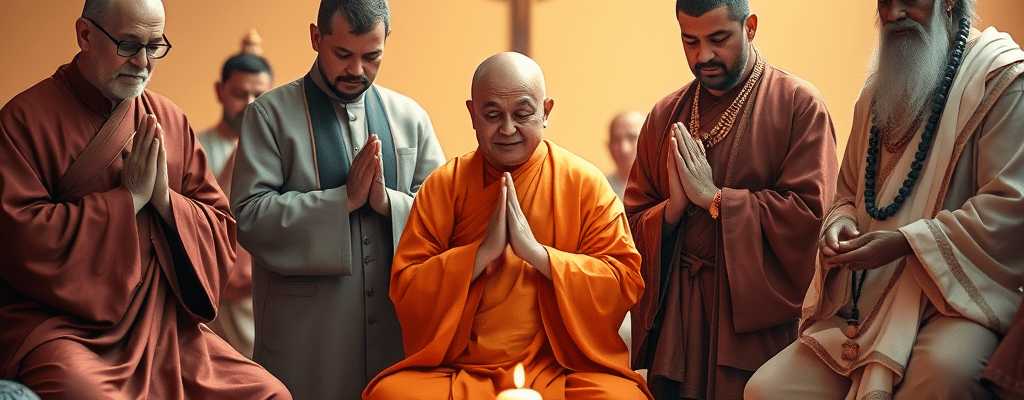

Have you ever seen Buddhist monks or nuns quietly participating in an interfaith gathering, joining hands or bowing their heads alongside those praying to a God or other deities? A common question arises: Are they betraying Buddhism? Are they, even inadvertently, praying to a foreign deity?

This concern, while understandable, stems from a fundamental misunderstanding of Buddhist practice. To unravel it, we must look to Buddhism’s origins and its diverse expressions across history.

The Original Teaching: Guidance, Not Supplication

Foremost, in the earliest Buddhist teachings preserved in the Pali Canon, the historical Buddha, Shakyamuni, did not teach prayer to unseen beings for protection, fortune, or health. He did not advocate relying on the intervention of gods or goddesses. The core practice was one of self-responsibility: meditation, ethical conduct, and the cultivation of wisdom to understand the nature of suffering and liberation.

As one scholar notes, “Buddhists do not pray to any spiritual beings in the original context. The path is one of understanding cause and effect, not of supplication.”

The Bridge of Later Traditions

Yet, if you visit temples across Asia, you will see many Buddhists engaging in what looks like prayer—making offerings before statues, reciting petitions to compassionate figures like Avalokiteshvara. This is the evolution of tradition. Schools of Buddhism that developed centuries after the Buddha’s passing incorporated these devotional practices. They often served as a skillful bridge for those accustomed to devotional prayer, providing a familiar starting point from which to gradually deepen understanding of meditation and wisdom.

So, What Are They Doing in an Interfaith Prayer Circle?

When a modern Buddhist—monastic or layperson—stands respectfully alongside people of other faiths, what is occurring internally? If they are chanting, it is likely a traditional text that recollects the Buddha’s teachings or expresses universal aspirations for peace. If they are in silence, they are often engaged in meditation: cultivating mindfulness, radiating loving-kindness (metta), or practicing compassion.

There is no internal conflict, no sense of spiritually battling a “foreign god.” The mindset that fears

- Buddha might be offended,

- or that one faith must triumph over another,

is seen as a reflection of a “differentiating mind” and personal insecurity. It reflects on the mental immaturity of that individual.

For a Buddhist with wisdom, the various belief systems (aka religions) are understood as human-crafted vessels attempting to convey profound truths about the human condition.

Focusing on Substance Over Form

Buddhism ultimately encourages looking beyond the form of ritual to the substance of the qualities being cultivated. The substance Buddhism treasures is various virtues. Such as the immeasurable loving kindness, compassion, appreciative joy, and equanimity. Also qualities such as generosity , ethics, patience, diligence and endurance, peaceful and stable mind, wisdom, etc.

The Buddha is revered not as a god, but as a being who fully perfected these universal qualities. He is awakened and has transcended the pitiful conditions that we are trapped in.

Crucially, the tradition holds that he cultivated these qualities over countless lifetimes, not necessarily while identified as a “Buddhist.” He could have been of another faith, or even another species. Therefore, the ultimate goal is not a label, but the perfection of these virtues.

In that manner, a monkey we see today can be a Buddha in the future. Likewise, our brothers and sisters of another faith.

A Shared Journey Toward Goodness

From this perspective, anyone—regardless of religion, race, or background—who is genuinely cultivating love, compassion, wisdom, etc is walking a path that Buddhism recognizes and celebrates. The journey toward wholesome values is a universal human journey.

This is why Buddhists will readily say “yes” to participation in good deeds, kind speech, and shared moments of reverence for peace. They naturally say “no” only to invitations toward unwholesome actions.

Loving-kindness is not a proprietary Buddhist asset; it is a universal capacity.

As one practitioner explains, “There is no fear that the loving-kindness of another religion will swallow you. The love a Buddhist strives for is all-encompassing. It is not biased and merges with all that is wholesome.” In this way, love becomes expansive enough to contain and honor the sincere devotion of brothers and sisters of all faiths.

The image of the Buddhist in silent meditation amid the prayers of others is not one of concession, but of profound solidarity—a recognition that beneath the diverse forms of our seeking lies a shared aspiration for a better, kinder world. A wanting to be free of suffering.

May all be well and happy.

Categories: Articles

I am just an ordinary guy in Singapore with a passion for Buddhism and I hope to share this passion with the community out there, across the world.

I am just an ordinary guy in Singapore with a passion for Buddhism and I hope to share this passion with the community out there, across the world.